Guide to Swahili street

slang in Stone Town,

Zanzibar

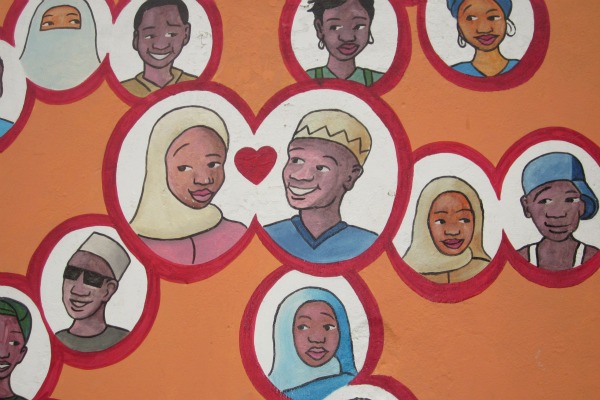

All photos by author.

Mambo! It’s the classic street slang for “what’s up?”

in Stone Town,

Zanzibar and in most of urban East

Africa. It literally means, “things” or “issues”?” The upbeat term

is often paired with the word vipi (how)

as in, Mambo, vipi? How

are things?

There

are at least 20 ways to answer the popular question that I never learned in

formal Swahili classes. The gap between school

and street could not be wider than in Stone

Town, Zanzibar’s capital city, a UNESCO World

Heritage site, that nearly 400,000 residents call home. Here, the lugha

ya kisasa “slang” or lugha

ya mitaani “street

language” changes by the minute, mostly by young people who flip or shine an

old word, or fashion a completely new one, inspired by hyper-local contexts,

meanings, and realities.

I

thought I knew Kiswahili. I’d earned an “advanced” certificate at the State

University of Zanzibar. The program prides itself on teaching a kind of Swahili

described as sanifu(standard) or fasaha (clean). It was rigorous and foundational,

but it left me speechless (more like a “beginner”) every time I left the

classroom and headed down Stone

Town’s boisterous

streets, where social greetings happen at every corner and turn. You really

can’t walk from point A to point B in Stone Town

without getting involved in greeting loops with friends and strangers alike.

Perhaps

the gatekeepers of Standard Swahili do not want to accept that Stone Town youth

have been and continue to be deeply influenced by Sheng – a kind of Swahili ‘patois’ that

developed by urban youth in Eastern Nairobi in the 1970’s and spread, overtime,

into all realms of East African life as a legitimate form of expression. While

most Zanzibaris still speak a more formal Swahili, youth here are tapped into

regional and global influences like music, film, and fashion that daily change

the contours and textures of street Swahili. The most immediate example of that

lives within the brackets of Swahili

street greetings.

|

Not greeting

someone, especially when they greet you first, is often seen as a straight-up

insult, if not a totally rude and ignorant act explained only by the cruelty

of a changing, globalized world.

|

Maamkizi (greetings) are a major part of Swahili culture. Not

greeting someone, especially when they greet you first, is often seen as a

straight-up insult, if not a totally rude and ignorant act explained only by

the cruelty of a changing, globalized world. It’s true, the extended greeting

is old-school, a shout-out to simpler times, when everyone had and/or took the

time to truly acknowledge who they were passing on the street.

Everyone

learns lugha ya heshima –

language of respect — which is a detailed, hierarchical system of greetings

depending primarily on age but also on status. The official way to greet,

depending on who you talk to and where, happens at least five different ways,

often accompanied by hand-shaking, hand-kissing, or at least a wave.

1. Shikamoo! Marhaba

For young greeting the old

“I hold your feet” “You are welcome [to do so].”

2. A-Salamu Alaykum! Wa-alaykum Salaam

A Muslim greeting

“Peace be upon You!” “Upon You, Peace.”

3. Hujambo? Sijambo

For greeting your peers/equals

“You don’t have an issue?” “I don’t have an issue.”

4. Habari yako? Nzuri (sana)!

Again, for peers/equals, everyone

“Your news?” “Good (very)!”

5. Chei-chei? Chei-Chei!

An endearing exchange initiated by a child to

any adult, usually accompanied by a handshake and small curtsy

These greetings all have their appropriate,

predictable follow-up questions about work, home, family, and health. Enter the

street-realm, though, and you hear a spicy mix of playful responses that

usually get lost on the tourist, who feverishly studied the back of a guide

book that couldn’t possibly capture the live, changing Swahili on the streets.

Stone Town’s

greeting culture is an essential part of anyone’s experience in Zanzibar, whether you

stay for a day or a lifetime. I wanted to get it right, but every time I tried

to throw down my textbook greetings, I got the pity-smile, followed by a flash

word-flood, a whole slew of fresh words thrown out as a string of slang.

I often had no idea what people were saying or

what they meant, until I really listened. After a while, I got used to the way

words arrive fresh like bread on the street each day — you gotta grab a hunk of

what’s hot and speak it, share the loaf.

This is the kind of Swahili that will make

your mabibi na mababu (grandmas and grandpas) cringe. It’ll make your

professors hang their heads down low, shaking with dismay. It’ll alarm police,

leaving them to think you’re ballsy, disrespectful, or clueless. But for most

people, it will definitely give you some cultural cache, local clout, or urban

charm.

Each word is a wink-wink of belonging.

So

here’s my quick guide to 20 of the hottest ways to respond to Mambo,

vipi?! next time

you’re in Stone Town:

1. poa

The universal way to say “cool!” but it really

means “recover” “calm” or “warm” (as in food that’s not too hot to eat)

Variation: poa

kichizi (kama ndizi) — crazy cool (like a banana)

2. shwari

A

nautical reference meaning “smooth/even” to describe the quality of the waves.

When there are no rough waves or wind, the sea is nice & smooth, easy to

travel. To say shwaremeans life’s journey is smooth like the sea.

3. bomba

Means “awesome!” It could also mean

“beautiful” or “nice” which some say was first used by Italian sailors (“bomb”)

and then transformed over time. It literally means “pipe,” which possibly refers

to an older Swahili-slang drug references like “syringe” used in Nairobi, Kenya.

Here in Stone Town, it’s another way to say, “Life’s

awesome, fantastic.”

4. bombom

As in “bomb,” “bombshell” or “machine gun.” It

also refers literally to “influenza” or “pneumonia” but in terms of greetings

can playful mean life is “killer” “hot” or “sick.”

5. rasmi

Means “official” — as in, everything’s good

because they’re in order.

6. safi

To say things are safi is to say you have a clean heart, life’s

good, no dirty business going on in your life. It literally means “clean,”

“clear” or “pure.” It also might be used to say that things are “correct/in

order.”

7. salama

Means “peace,” as in, all’s well, peace

prevails, no fighting with anyone or anything. The word itself is derived from

the Arabic word, salam.

8. mzuka

Literally means “worry,” “desire” or “moral.”

As a figure of speech, it’s been associated with the sudden, pop-up appearance

of a spirit or ghost. Oddly enough, through various hip-hop lyrics, the word

has a totally different meaning: it’s now used on the streets to mean

“excellent” or “fantastic.”

9. freshi

Slang for the English word “fresh,” sort of

related to safi.

It’s derived from global hip-hop vocabulary, whereby anything “fresh” is really

new and good.

10. hamna noma

A favourite with Stone Town

youth, it means, there is no “obstacle” whatsoever — no problems at home or

anywhere.

11. kama kawa

Shorthand for “kama

kawaida” that translates to “like usual.”

12. kiasi

The word means “size” or “moderate amount” and

is often heard in the markets or when talking about a purchase. To say kiasi in

a greeting means eh — I’m fine.

13.wastani

Similar to kiasi, meaning “standard” or

“average” as in, eh — fine, not good or bad, just here.

14. mabaya!

Means “bad!” as in, truly, things are not

going well, or playfully, things are going so bad, they’re good. In a culture

that doesn’t officially permit the expression of negative feelings in public,

this slang is a playful chance to vent without being taken too seriously.

15. mzima

Usually refers to the body’s state of health

and well-being, literally meaning “full” or “whole.” This is actually a

“standard” response but if you say it with enthusiastic pop, it takes on a

street flavour.

16. mpango mzima

Means “full plan” as in, “I have my act

together” or “’I've got it all figured out.”

17. fiti

Literally comes from the English word “fit” as

in physically healthy, but is used to mean that life itself is fit and strong.

18. shega

Another way to say “cool” literally meaning “fine”

or “nice.”

19. kamili

“Complete,” “perfect,”” “exact” or “precise.”

20. hevi

Literally means, “heavy” as in the English

word, to signal life’s intense, deep, or a burden.

If you

tag the word sana (very) orsana, sana (very, very) to the end of most of

these words, you’ll stretch their power and sentiment. Example: Bomba

sana!

Hitting

the word with kabisa(totally) will punctuate the sentiment, giving

it some verve. Example: Freshi kabisa!

Adding

the word tu (just)

to the end of most words will cut the effect a bit, sending the message that

the state you described is just that, nothing more, nothing less. Example: Poa,

tu or Freshi,

tu.

Doubling

some words will give your sentiment extra power. Example: poa-poa, freshi-freshi,

or bomba-bomba. You should probably save this, though,

for when things really are going extremely well for you.

Mambo! reigns supreme as the number one way to strike up a

street-and-greet. But usually, if time allows, people end up showing off a kind

of linguistic fireworks where, through the prompting of various other ways of

saying “what’s up,” they get to rattle off two, three ad infinitum questions

and answers in a single breath. It’s kind of like greetings-acrobatics.

So,

beyond the initial Mambo! here

are a few other ways to keep the conversation rolling naturally (that also hold

their own as conversation kick-starters):

1. Hali, Vipi? Hali? or Vipi, hali?

Literally means, “condition, how?” or “how’s

your condition?”

2. Je/How forms:

Inakuwaje? – How is it?

Unaendelaje? – How’s it going?

Unaonaje? – How do you see things?

Unasemaje? – How do you say it?

Unajisikiaje? – How do you hear/feel?

3. One-word prompts:

Vipi! Literally means, “how?”

Habari! Literally means, “news?”

Sema! Literally means, “say!”

4. Lete/Bring forms:

Lete

habari! – Bring the news!

Lete mpya! – Bring

what’s new!

Lete stori! – Bring the story!

Lete zaidi! – Bring more!

5. Za/Of forms:

Za

saa hizi? – [of] the moment?

Za siku? – [of] the day?

Za kwako? – [of] your place?

This greeting thing could go on and on,

spiralling into story-sparring and reminiscing, politicking and lamenting. If

you really have to wrap up a long loop, though, there are a few classics that

have withstood the test of time.

Take a

deep breath in, sigh, offer out your hand for a shake or a Rasta-style

fist-pound, and then say haya, baadaye (okay, later!) or haya,

tutaonana! (okay,

we’ll see each other!). If you need to offer an explanation, simply saying niko

busy (I’m busy) or nina

haraka (I’m in a

hurry) usually does the trick. And then you’re off! That is, until you meet

someone else on the street, and the greeting game starts all over again with an

equally upbeat, mambo, vipi?!By the time you read this, it’s possible

that 20 new words are flip-flopping around, going through try-outs and

show-times.

The most popular end-phrase in a greeting loop

on the island of Zanzibar is the timeless:

Tuko

pamoja – We’re [in this]

together.

The heart-felt sentiment, echoed back and

forth between greeters at the end of any Stone Town street-and-greet, really

does say it all.

Tuko

pamoja.

Haya,

niko busy – baadaye.

ABOUT THE

AUTHOR

Amanda

Leigh Lichtenstein

Originally from Chicago, IL, Amanda currently lives in Stone

Town, Zanzibar, where she works as the Resident

Director of a Swahili Overseas Flagship Program at the State University of

Zanzibar. When she's not obsessing over kanga textiles or Kiswahili proverbs,

she's experimenting in the kitchen or traveling along the Swahili coast. Her

writing most recently appears in Mambo Magazine and Contrary Magazine.